Sauce foundations

Sauce foundations are the essential building blocks of successful cooking. Whether you are preparing a simple pan sauce to finish a protein or crafting a complex warm sauce to dress vegetables and grains, understanding the core principles gives you control, consistency and creativity. This guide explores the fundamental techniques and flavor logic behind great sauces and shows how to apply them in home and professional kitchens. For more recipes and ideas visit tasteflavorbook.com to expand your repertoire.

Why sauce foundations matter

Sauces do more than add moisture. They enhance texture and shape the way flavors are perceived on the palate. A sauce can unify disparate elements on a plate, balance richness with acid, and add visual appeal. Learning sauce foundations reduces waste and helps you rescue dishes that might otherwise seem flat. When you know the emergency moves to thicken, brighten or season, you can turn a simple meal into a memorable one.

Core components of sauces

Every sauce has a few primary components. Recognizing these components helps you build sauces from scratch and troubleshoot problems.

- Liquid base. Typical liquids are stocks, broths, dairy, wine or even water. The base determines body and flavor depth.

- Thickener. Thickeners include starches such as cornstarch and arrowroot, reduction of the liquid, emulsifiers such as egg yolk or mustard, and roux or beurre manié for butter and flour binding.

- Fat. Butter, oil and animal fat carry flavors and create a silky mouthfeel.

- Acid. Vinegar, citrus juice or wine lift the sauce and balance fat.

- Seasoning and aromatics. Salt, sugar, herbs, garlic and spices personalize the sauce and highlight the main ingredient.

Classic techniques to build sauce foundations

Mastering a small set of techniques unlocks many sauces. Learn these and you can adapt them with little risk.

Reduction is the most straightforward move. Simmer the liquid until water evaporates and flavors concentrate. Reductions create glossy sauces with intense taste suitable for both meat and vegetable dishes.

Emulsification binds water based components with fat. A simple vinaigrette starts as a temporary emulsion but can be turned into a stable sauce by whisking in a binder such as mustard or by slowly incorporating oil into egg yolks for a richer result.

Roux is flour cooked in fat. It thickens sauces while adding a toasty note. Cook longer for a darker roux with a nuttier flavor. If you prefer a quicker finish, beurre manié is a soft paste of flour and butter worked together then whisked into hot liquid to thicken without long cooking.

Egg based thickeners provide silkiness for warm sauces. Tempering is key. Slowly add hot liquid to beaten yolks while whisking to avoid coagulation then return the mixture to low heat until the sauce coats the back of a spoon.

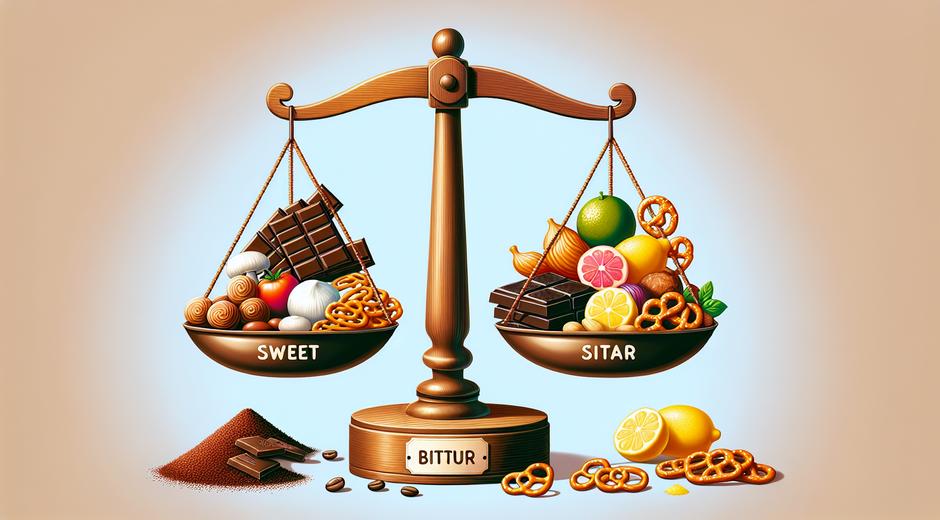

Balancing flavor and texture

Balance is the signature of a memorable sauce. Taste as you go and use acid to brighten and salt to define. A touch of sweetness can smooth sharp edges while herbs and aromatics add freshness. Texture matters too. Consider whether you want a light pourable sauce or something spoonable and coating. Adjust thickness with reduction or a light slurry of starch if needed.

Seasoning strategies

Seasoning early and adjusting at the end produces the best results. Salting at the beginning builds flavor as the sauce reduces. Finish with a final adjustment after reduction and cooling because flavors concentrate. A bright element added at the end such as lemon juice or a splash of vinegar can transform a dull sauce into one that sings.

Pairing sauces with foods

Think of sauces as partners to the main element. Rich meats often pair well with acidic and herb driven sauces. Delicate fish benefit from lighter, aromatic sauces. Root vegetables take on bold flavors and can handle both savory and sweet notes. The key is to match intensity and texture. A heavy cream sauce can overpower a mild protein while a thin vinaigrette might not be satisfying with a hearty roast.

Vegetarian and vegan sauce foundations

Modern plant based cooking relies on layered flavors to make sauces compelling. Use roasted vegetables, mushrooms and dried seaweed to build umami. Plant milks, nut creams and blended beans provide body. For emulsions, aquafaba and mustard are powerful binders. Nutritional yeast adds savory depth and boosts mouthfeel without dairy. For high quality ingredients and natural extracts consider reputable suppliers that share sustainable values such as BioNatureVista.com for ingredient inspiration and options.

Troubleshooting common problems

Curdled sauce. When egg based or dairy sauces split, remove from heat and whisk in a spoonful of cold liquid to cool and bring it back together. Re tempering slowly often saves the sauce.

Too thin. Simmer to reduce or whisk in a small amount of slurry made from starch and cold water. For emulsified sauces, whisk in a touch more emulsifier like mustard or an egg yolk to stabilize.

Too thick. Gradually whisk in warm stock or water until you reach the desired consistency. Avoid adding cold liquid directly to a hot sauce as this can shock the emulsion.

Storage and safety for sauces

Store sauces in airtight containers in the refrigerator. Most dairy and egg based sauces should be used within a couple of days. Acidic sauces such as vinaigrettes last longer. Freeze sauces that hold up to freezing, such as broth based ones, but avoid freezing emulsions that are dairy heavy as texture changes can occur. Reheat gently and finish with a final seasoning check.

Simple sauce templates to practice

Keep a few reliable templates in your culinary toolkit and adapt them with herbs, aromatics and spices.

- Brown sauce template: start with pan fond and brown stock. Deglaze with wine or vinegar. Reduce and finish with butter for gloss.

- White sauce template: make a roux with equal parts fat and flour, add warm milk or stock slowly and whisk until thick. Season and finish with nutmeg or lemon.

- Emulsion template: whisk acid and seasoning, slowly stream in oil while whisking until thick. Adjust tang with more acid or add mustard for stability.

- Veloute template: use light stock and a blond roux to create a smooth base that takes on many flavor profiles.

Developing your personal sauce language

Experimentation is the final ingredient. Start with a template, then add a single new element each time you practice. Keep notes on proportions and toast times. Over time you will develop a shorthand for flavor direction such as more acid, more fat, or longer reduction. This shorthand lets you consistently recreate successes and quickly correct mistakes.

Conclusion

Mastering sauce foundations empowers you to elevate everyday cooking into dishes that are balanced and memorable. With core techniques such as reduction, emulsification and thickening in your skill set you can adapt to ingredients in season and dietary preferences. Remember to taste and adjust, focus on balance and keep a few reliable templates on hand. For ongoing inspiration and practical recipes return to tasteflavorbook.com and continue building a library of versatile sauces that reflect your style.